by Matthew Smith

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Social Work faculty, staff and students tackled difficult but important topics during the School’s third installment of its Black History Month Research Series.

Sponsored by UNC’s Global Social Development Innovations Center (GSDI) and the INSPIRED Lab, this year’s series featured seven speakers during the month of February with more than 1,600 registered participants.

“Each year, we observe growth and a clear demand for the Black History Month Research Series from researchers and practitioners across the country,” said Trenette Clark Goings, the School’s Sandra Reeves Spears and John B. Turner Distinguished Professor and founding director of the INSPIRED Lab. “We are delighted to offer this series annually as a strategy for enhancing researcher, practitioner and policymaker knowledge and skills and ultimately helping UNC to achieve its mission of solving the world’s greatest problems with a primary focus on enhancing the quality of life for North Carolinians.”

While introducing Williams, Goings shared the toll that racism takes on a country.

“Racism takes its toll on all of us,” Goings said. “If we want to achieve optimum health for all Americans — and I believe we do — we must uproot the racist beliefs, practices and structures that lie at the heart of our health, employment, criminal justice, and housing systems and policies.

“Racism, whether it’s implicit or explicit, is a virus that is making us sick.”

During his presentation, “The Virus of Racism: Understanding Its Threats and Mobilizing Defenses,” Williams shared powerful statistics about the excess deaths of Black people and the reasons marginalized populations face adverse health outcomes even when adjusting for education and economic status.

Williams remarked that from 1999 to 2020, there were more than 1.63 million excess Black deaths — people who would not have died if the health of Blacks and whites were equal — totaling 203 daily deaths.

“A massive loss of life,” Williams said.

Williams added that research has shown that even when accounting for socioeconomic status, Black people have lower life expectancies than whites. When comparing the life expectancy of Black people against their white peers, it appears race matters at every level of income and education.

“Racism and racial discrimination play a role in health outcomes on physical and mental health,” he said. “Racism is the critical missing piece of the puzzle to understanding the patterns of racial disparities in health.”

Segregation, Williams said, has been the central driver of the large racial and ethnic differences in socioeconomic status, leading to poorer health overall for Black people. He added that segregation has led to less access to resources, higher exposure to stress, and more exposure to chemicals and environmental racism.

“Segregation (and) racial inequalities do not reflect a broken system,” Williams said, “but a carefully crafted one.”

Williams offered three strategies to help close the health equality gap, including:

- Increasing the impact of medical care — meaning medical access to all — improving quality of care, diversifying the workforce, and providing care that addresses social context;

- Identifying and supporting protective factors and resilient resources, including caregivers, peers and community leaders; and

- Creating communities with opportunities to minimize, neutralize and dismantle racist systems, like enriching neighborhood environments, increasing economic development opportunities, and investing in early childhood education.

Recordings of all four sessions can be found online on the School’s Vimeo page.

A recap of other series sessions is provided below.

Black youth and mental health

The second BHMRS session focused on Black mental health, particularly Black youth mental well-being.

Moderated by Assistant Professor Orrin Ware, the session featured University of Maryland at Baltimore Associate Professor Theda Rose and University of Michigan Associate Professor Camille Quinn who discussed mental health, well-being models, and potential interventions to improve mental health diagnosis and care.

“There has been a focus on deficit-based narratives,” Rose said. “What’s missing. It focuses solely on problems and does not give you a full picture of Black adolescent development.”

Rose’s research uses a dual model of mental health, not just looking at pathology — disorders and diagnoses — but well-being. This allows social workers and mental health advocates to care for vulnerable groups that may be ignored or neglected because, as she put it, they do not “fit into a certain bubble.”

Overall, she’s found that putting an emphasis on well-being, considering conceptual and cultural mental health indicators, and putting adolescents at the center of the conversation about their mental health has benefitted marginalized groups.

Quinn’s research focuses on an even more focused population — Black girls at the intersection of race, health and law-breaking behavior who are involved in the youth punishment system.

Quinn shared that girls comprise a growing number of youth arrest rates, despite overall numbers dropping.

“I didn’t realize the level of criminalization that was happening to Black girls in communities like mine where I grew up,” Quinn said. “That was the impetus for me to investigate further, not just as practitioner, but eventually as a scholar.”

Quinn said that this subpopulation became a focus because it was underserved and understudied. Her research has examined four main factors that contribute to mental health adversity, including post-traumatic stress, substance misuse and sex under the influence, relationships with adults and peers, and simply living as a Black woman.

“We have to look at the protective factors,” Quinn said. “How do we support Black girls?”

Her current work analyzes how creating opportunities for healing with mindfulness-based stress reduction interventions with justice-involved Black girls and their parents and care givers can improve mental health.

Supporting the Black community

The third session saw Associate Professor Rainier Masa introduce Sonyia Richardson, UNC Charlotte assistant professor, and Von Nebbitt, Morgan State University School of Social Work associate dean for research, to the series.

Nebbitt shared the history of the development of Black communities and the role public housing has played, while Richardson discussed a major topic affecting Black youth — suicide.

Richardson noted that Black youth suicide stats have continued to increase, now reaching the highest rates for any group. While non-Black populations tend to see suicides at higher ages, younger generations of Black youth are dying out compared to their peers.

I hear them say, ‘No one even cares about us;’ or ‘Our kids don’t seem to matter when it comes to mental health interventions.

— Sonyia Richardson, UNC Charlotte assistant professor

“Oftentimes we talk about what evidence-based practices there are and what evidence-based practices are (clients) receiving,” Richardson said. “That’s important, yes. But I would add on to that: Are we adding an element of humanizing first?”

Richardson said that qualitative feedback that she’s received focuses on the need for providers to humanize Black populations first before providing interventions or care.

“I hear them say, ‘No one even cares about us;’ or ‘Our kids don’t seem to matter when it comes to mental health interventions,’” Richardson said.

She shared three interventions that her research is currently supporting in the Charlotte, North Carolina, area, including:

- ASPIRE Community Capital: A 12-week program that helps BIPOC people in Charlotte who are starting, growing and sustaining private behavioral health care practices. The goal is to support providers and help them get their businesses off the ground to create a pipeline of diverse mental health providers.

- Village HeartBEAT: A faith-based, nonprofit community engagement initiative that has created mental health hubs in local Black communities that bridge individuals to mental health care. The program connects individuals to community members they trust to help them find the mental health assistance they need, whether it’s therapy or non-clinical services.

- CA-LINC: A suicide detection and intervention model for black youth created by the Black community for the Black community. Richardson is currently conducting open trials to test the intervention.

Following Richardson, Nebbitt gave a history and overview of public housing in the United States and how changes to the program affected Black communities.

He shared policies that profoundly affected how Black and white neighborhoods were segregated during Jim Crow and how those policies affected the racial wealth gap.

“In the beginning many white families lived in public housing,” Nebbitt said. “Now nationwide, it is 95% a Black experience. In the early days it was not. To have this was a special thing. It was looked at as a solution to a social problem.”

At the onset of the public housing boom, Black and white populations were similarly represented in communities.

“It came from the idea that every working family should have a house,” Nebbitt said.

Public housing was seen as a multi-purpose policy solution: Providing public work, clearing out slums, and meeting a growing need for urban housing.

However, Nebbitt explained that policies developing during Jim Crow — a period of enforced racial discrimination and segregation — changed that. The Housing Act of 1949 strongly benefitted white families, authorizing the development of the Federal Housing Administration, the Veterans Administration, and the Farmers Home Administration. These organizations helped provide finances and mortgages for white families that built the country’s modern-day suburbs, while neglecting to provide funding for non-white families.

As a result, public housing declined due to white flight and an exodus of working-class Black families, changing the program’s income profile, racial profile, operational cost, and physical development.

As public housing became more and more black institution, the political will to do something changed.

— Von Nebbitt, Morgan State University School of Social Work associate dean for research

Other social forces continued to marginalize public housing, including turning the program from a progressive program into a social welfare program; political and cultural forces stigmatizing and degenerating public housing; and media stereotyping of public housing.

While some national responses have helped redevelop public housing, Nebbitt said research-based efforts need to help shift “from a problems mindset to a solutions mindset.” He said putting a focus on community correlates of physical health; learning how families benefit from past responses to public housing; and leading qualitative research to learn how families have succeeded and survived in public housing can take initiatives from deficit-based responses to ones focused on capacities and strengths.

Nebbitt added that a major change could come from transitioning participants in low-incoming housing programs to home-buying programs as income levels increase.

African ancestry and mental health

The series closed with insights into international mental health care, as University of North Texas Professor Elias Mpofu and University of Ghana Research Fellow Lily Kpobi provided a look into African-centric care.

Mpofu explained that the African way of looking at mental health care includes looking at the context of the symptoms — the life situations and personal changes around the person seeking treatment.

“It’s a much more pragmatic approach,” Mpofu said. “We work from outside, in.”

He shared common research agendas for health well-being in an African context that may lead to more effective treatments and interventions:

- Health antecedents including collective beingness (interconnectedness, inclusive lifestyles, holistic living) and spirituality (divine order of thing, ultimate life purposes);

- Sources of maladjustment including relational discordance (human, spiritual, natural, world, bodily);

- Recovery activation agents including ceremonial practices (rituals, ways of knowing, intuition and reciprocity); and

- Treatment goals and processes including symptom relief (naming, expectation and symbolism) and personal and situation change (cleansing, scarification, moral, consciousness and collective insight)

Mpofu closed with his belief that those with African ancestry have what it takes to take care of their health and wellness. With a person-centered and humanistic approach to mental health, Mpofu believes an empowered mental health counseling strategy in life situations works for everyone.

“Think about what people can do, what they do do, and their choices,” he said.

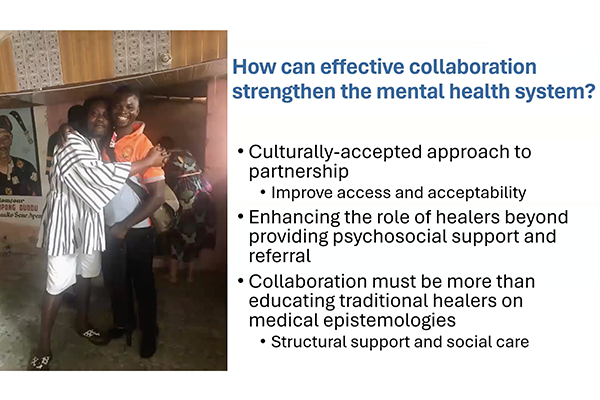

As community members used multiple approaches to mental health care, Kpobi and her research team sought to learn more about how traditional healers factor into care.

“There’s a drive to understand how we can harness available resources that we have because we do have a limited number of mental health professionals that are formally trained biomedical professionals,” Kpobi said. “However, there are a large number of faith-based healers.”

She shared that traditional healers fill gaps in health care, are easier to access, often hold congruent beliefs with their patients, and take a social approach to care that can be more appealing.

Collaboration between traditional healers and medical professionals can have benefits, Kpobi said, ranging from making space for cultural and religious practices in mental health care, decentralizing care away from institutions and putting it back into the community, and an overall increase in follow-up care and support.

Kpobi added that there are challenges that need to be overcome.

“Traditional healers have often been ridiculed,” Kpobi said.

Healers may often be suspicious about the intentions of health programs and workers. Kpobi noted that coming in with a humble and respectful approach to partnership is key.

“We had to look at how (we) did community entry,” she said. “Because we had to recognize that we needed to enter their space. Sometimes it meant approaching them like we were a child approaching an elder. We did come to tell them … but we came with what we could learn from them.”

Kpobi said mental health care is still very much dominated with the idea that westernized medicine is better than traditional.

“However, we need to learn from traditional systems the same way they learn from us,” she said.