by Susan White

During the last few years of Antoinetta Cash Royster’s 16-year-career with the Department of Social Services in Person County, many of her conversations with colleagues and community partners centered on one major topic: How could the county strengthen its child welfare system to ensure that children who had survived abuse received needed services in a timelier manner.

Although the county had grown in the last three decades into a bedroom community for workers in the healthcare industry in nearby Orange and Durham counties, specialty services in mental health and trauma-informed care were still limited. Such resources were vital for child abuse investigations and without access to trained specialists, social workers and law enforcement officers often had to look to neighboring counties for help.

In some cases, to ensure that time sensitive medical and forensic examinations were completed, local sheriff’s deputies or a social worker might even have to drive a child victim nearly an hour away to the nearest facility with doctors and mental health professionals trained to conduct needed physical examinations and interviews with children.

“Sometimes, you could get a child in pretty quickly,” explained Royster, MSW ’13, a retired Person County child welfare worker, child protective services investigator, human services evaluator, and social work program manager. “But even then, quickly might still mean a couple of days. Depending on where you were going, it might also be the next week and sometimes follow-up interviews had to be scheduled three weeks out. Ultimately, you want them to be seen as soon as possible because you don’t want to lose any medical evidence.”

“Sometimes, you could get a child in pretty quickly,” explained Royster, MSW ’13, a retired Person County child welfare worker, child protective services investigator, human services evaluator, and social work program manager. “But even then, quickly might still mean a couple of days. Depending on where you were going, it might also be the next week and sometimes follow-up interviews had to be scheduled three weeks out. Ultimately, you want them to be seen as soon as possible because you don’t want to lose any medical evidence.”

Thanks to Royster’s commitment to her home county and key agency partners, children of suspected abuse and their families no longer have to wait for critical services. Earlier this year, a committee led by former district attorney Jacqueline Perez, along with Royster, colleagues at Person County DSS, and nonprofit agencies CrossRoads and Roots and Wings, officially opened the county’s Child Advocacy Center (CAC), a community-based, child-friendly center in Roxboro that offers multidisciplinary services for children and families affected, primarily by sexual abuse. Services are aimed at reducing trauma and are free of charge. Currently, 51 such centers operate across the state; CrossRoads manages three.

“This really was a group effort,” said Ronnie Dunevant, director of the communty advocacy program Roots and Wings. “Antoinetta and I were fortunate to be on the committee and our energy was needed, but it was a group effort.”

CrossRoads operates Person County’s new center and received unanimous support from the board of commissioners along with $100,000 in start-up funding, which helped to support the center’s initial operating expenses. The nonprofit also received an outside grant to renovate the center’s windows and to improve parking. CrossRoads worked closely with the property owner, who generously agreed to pay for other renovations to ensure that the home, which had fallen into deep disrepair, was transformed into a pleasant and inviting space.

Most driving by the house today likely will never see the important work going on inside. To protect the sensitivity of clients, there are no signs outside advertising the center’s existence. Equally as much care went into making the interior space safe and comfortable. Just past the lobby area with calming blue walls and a stylish couch and chairs, a playroom with a child-size couch awaits along with a cubby of colorful toys, crayons, and coloring books.

To the left of the kitchen is the center’s interview room with a cushy chair and built-in corner bookshelves filled with stuffed teddy bears. Nearby is a paneled conference room with a video monitor and recording equipment — necessary tools connected to the interview room for gathering evidence in a non-obtrusive way.

“I still can’t believe it’s here,” Royster said on a sweltering day in June as she stood in the center’s lobby. “I just remember us coming in here before it looked like this, and walking through and envisioning where everything was going to go and what we wanted this place to be.”

Dunevant understands Royster’s enthusiasm better than anyone. Before Royster retired in 2021, the colleagues had long operated in similar circles. Both served at-risk youth and families in a county where according to the nonprofit NC Child, some 44% of children are growing up in households with limited incomes and at least 10% of the county’s nearly 40,000 residents lack health insurance.

Then, a few years ago, the colleagues noticed a slight increase in child maltreatment reports. Whether the uptick was attributable to a rise in cases of abuse or to an increase in reporting was unclear. But what Dunevant and Royster could see was the community’s need for additional support, including for specially trained professionals certified to handle child abuse investigations. Such vital resources determine how quickly a case is resolved and justice is served for children already at-risk of further victimization.

“You can’t just interview a child the way you would any other victim,” Dunevant said. “First, you don’t want to reintegrate the trauma and second, you have to think about establishing evidence. Because any of these cases are probably going to take three to five years to come to fruition, that interview process needs to establish what eventually can be used in the court.”

Legally, when social workers are assigned cases where physical, sexual and other forms of child maltreatment are suspected, the first few hours of an investigation are critical. Board-certified pediatricians must perform non-invasive medical evaluations to gather any physical and cognitive evidence of trauma or abuse. To identify a perpetrator, a certified forensic investigator must also interview the child using a protocol that follows an ethical process and protects the child from further traumatization.

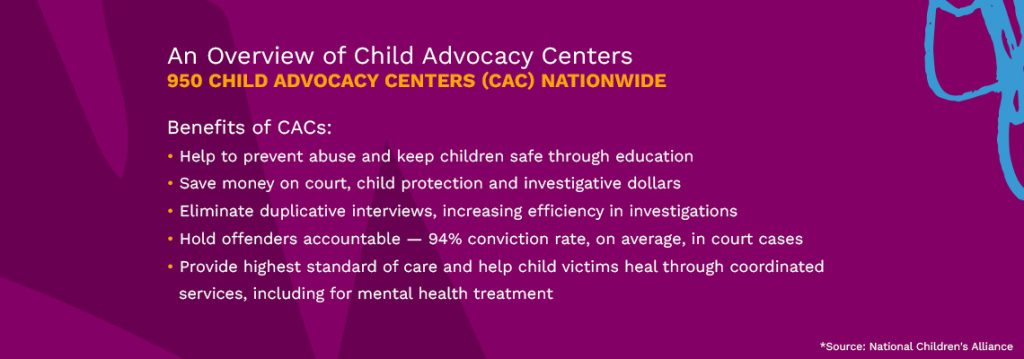

Child advocacy centers were designed to do just that. The National Children’s Alliance, the force behind a movement to keep children safe, oversees the country’s 950 CACs, which provide support, resources and education to help communities better understand child maltreatment.

Communities with CACs have already shown success, including better rates of coordination around investigations, an estimated savings in court costs, the elimination of duplicative interviews, and a higher percentage of successful prosecutions. In one study, communities with CACs had, on average, a 94% conviction rate in court cases.

Having advocacy resources in place to help families navigate available assistance long after a case is closed is also vital, Dunevant added.

“The traumas that these children experience sometimes can manifest itself in different ways depending on whatever the kid has going on and especially as they transition from puberty,” he said. “So there’s a constant need for advocacy, support and therapy to bring that kid along from wherever they are.”

Since opening in Roxboro in February, Person County’s CAC has already handled more than a dozen cases, including one involving child trafficking. For Royster and Dunevant, such cases are unimaginable but knowing that the county now has the additional resources and support in place to help children and families is key, they agreed.

For Royster, who continues to do volunteer work in retirement, further supporting her community is also important. Most recently, she worked with a committee that was developed to address the unhoused community in Person County. The committee recently secured $60,000 from the county’s board of commissioners to develop Person’s first emergency shelter. The shelter is expected to open in late 2025.

“I always said that I wanted to be beneficial to my community and to make an impact here because this is my home,” Royster said. “The people here invested in me, so I always knew that I wanted to give back to my community, whether that be for the children who have been traumatized or abused or for their families who also need support. Just being in a position to be able to offer hope means a lot.”